March 31, 2014

Monday

This is going on your permanent record!

— warning issued to everyone by every Sister of Mercy who taught at Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament School in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania from 1954 through 1961, at least.

We heard the pronouncement once or twice a day, sometimes directed at an individual, sometimes at an entire class. Your permanent record could be besmirched if you were tardy, or daydreaming, or reluctant when Sister assigned you to help redd up the cafeteria. The permanent record held your grades, your attendance data, your scores on aptitude tests. Negative notations there could threaten future employment. Who wants a worker who is often absent or tardy, who sneaks the poetry anthology onto her lap and reads during math drills, who does slipshod work wiping down the lunch tables?

I worried about my permanent record, certain that the times I requested a bathroom pass when all I really wanted was to get out of the classroom and be alone for maybe four minutes were engraved therein. And of course there was the terrible shame of the stolen book, a transgression I was sure would be discovered.

Your grade school permanent record would follow you into high school, where it would be read by and likely influence your new teachers, who would add to it. The combined dossier would follow you all the days of your life, to college, to jobs, probably all the way to the Pearly Gates, where St. Peter might peer at it, and ask about that time in 1964 when you failed to greet Mr. Williams (the band director) in the hallway. (You were angry with him because his failure to meet a professional obligation meant you couldn’t go to District Orchestra. Mother Francoise said this was no excuse, and you served a detention.)

As it happens, I know what my high school permanent record says about me, because a copy of it is lying here beside my keyboard. Although the detention is noted, along with the 12 times tardy and the 7 days absent that year, no reason is given.

Last week I visited the new site of Bishop McDevitt High School, my beloved alma mater, relocated from its iconic twin towers in the city to a sprawling state-of-the-art facility on a tract of land that GPS units can’t find yet. I’d been there only once, last year on the occasion of the first open house before the occupying of the new building. I had been to the final basketball game at the old gym the night before, an event so powerfully emotional for me I couldn’t even write about it here.

My visit last week was as a representative of the group that is planning the 50th Anniversary Reunion of the Class of 1965. I’ve undertaken the responsibility of bringing our contact lists and our memorial lists up-date, and of studying what of our history is represented in the archives. I was given a tour of the school in a much more personal and relaxed way than I had experienced as one of the many who, herded into large groups and led by a student who read from a prepared guide, were given a cursory walk-through last year. This time I saw the guidance suite, the cafeteria swirling with young energy, the chapel, the auditorium, the library (the library!).

I mentioned that I had once been pretty adept at helping students with college application essays, and that I missed that kind of work. I was introduced to the guidance counselor who helps students manage that process, shown the area where she hopes to establish a writing center. I left with the paperwork necessary to obtain the clearances needed to work with students as a volunteer, and an unofficial copy of my permanent record.

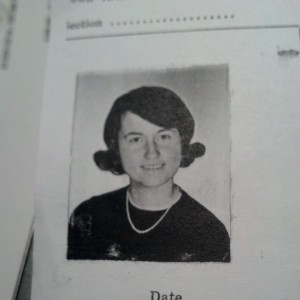

At left is the picture of me that is attached to the document. It was taken in the summer of 1964, for the yearbook. The sweater and the pearls belong to the photographer, and are the same items worn by every single girl in the class except one, who wore an heirloom strand that had belonged to her grandmother. That strand is undoubtedly a finer piece of jewelry than the one that was hanging from a hook in the changing room, but it’s also made of smaller pearls all the same size, and one sees instantly that it is different.

At left is the picture of me that is attached to the document. It was taken in the summer of 1964, for the yearbook. The sweater and the pearls belong to the photographer, and are the same items worn by every single girl in the class except one, who wore an heirloom strand that had belonged to her grandmother. That strand is undoubtedly a finer piece of jewelry than the one that was hanging from a hook in the changing room, but it’s also made of smaller pearls all the same size, and one sees instantly that it is different.

I remember that my picture had to be retouched because the hair that swoops down over my left eyebrow had defeated my efforts with hairspray to hold it. It had separated into three or four clumps, and made me look sweaty. I had most particularly asked the photographer not to let this happen. Every time I passed out a picture, I saw the sheen of the ink that had been applied to the negative. On the other hand, a classmate took to using a black inkpen to add a mole to the corner of her mouth — a “beauty mark” — that had been airbrushed out without her permission.

My permanent record did hold some surprises for me. My grades show a youngster whose achievement was far better than the miserable mediocrity I thought would be reflected there. I was constantly reminded at home that I was either stupid or pretending to be, that I was not working up to my capacity, and that I would be hard pressed to succeed in life if I didn’t change my ways. Yet my grades are all A’s and B’s, except for a disastrous junior year, where a sprinkling of D’s and even F’s meant that my class rank fell to the bottom half of the class.

Some of my teachers evidently thought I had room for improvement. Under “personal characteristics” there are several notations that I was “vacillating,” “co-operative but retiring,” only “somewhat dependable,” and in need of “occasional prodding.” One teacher has even noted that I was “apathetic” and “purposeless.” Nevertheless, I graduated only a few places out of the vaunted “upper fifth” of my large class.

A box labeled “Vocational Plans” has the following notations (the Roman numerals refer to what year I indicated said plan, “I” being ninth grade):

Hospital staff nurse I

Teacher II

Novelist III

Journalist IV

Remember that Year III was the year my grades fell, I was absent or tardy numerous times, and served a detention for being disrespectful. I can only assume that in Year IV I was advised that “journalist” paid better than “novelist.”

The biggest surprise, however, is found in the box for “Talents — Interests — Hobbies”:

Reading I, II, III, IV

Corresponding I, II, III, IV

Writing I, II, III, IV

Violin I, II, III, IV

Chorus I, II, III, IV

Hiking III

Hiking? HIKING?? That year, my apparently troubled junior year, the year I read Thoreau and then saw some Canada geese take flight from the middle of a creek, their wings dripping, and decided I wanted to be a writer, that year I did walk a lot to a cemetery about a quarter mile from my house, a neglected area with graves dating from the 17th and 18th centuries and none beyond the middle of the 19th, carrying a book, and a pad of lined paper, and a pen.

Nothing I wrote that year survives. My ambition to be a novelist, suppressed or ignored through forty of the fifty intervening years, does survive, resurrected and nurtured now.

As does my permanent record. When I asked for it, I expected the guidance office secretary to write down my request and ask for a payment so a copy could be mailed to me. For all I knew, it was in a vault somewhere, perhaps on microfilm or in some other space-saving form.

Instead, she rose and entered a narrow storage room near her desk. She walked along a row of file drawers, opened one, ran her hand along the rough, uneven edges of the manila folders wedged in there, and pulled mine out. Not a copy, not a facsimile, but the actual folder that various teachers and other school personnel had handled and written on during my four years as a student under their care.

I believe that we, and everything else on this earth and in this universe, are nothing but energy, organized for a time into the bodies that we carry and the landscapes that we move in. Some of our energy is retained in the places we have been. I thought about that a lot when I walked the halls of the Bishop McDevitt building I knew for the last time.

Holding that manila folder, knowing that it was among thousands of others covering the history of our school back to its founding in 1918, made me understand that part of who I was, who my friends and teachers were, was still alive in the new building. It had been carried there, along with the bronze donors’ plaque from 1930 and the Tracy Hall donors’ plaque from 1950 and the chapel donors’ plaque from 1962 we walked by every single day.

At that moment I let go of my grief at the loss of the building I knew. Before I left, I sat alone in the new chapel for a moment, and then went home to do more work on my novel.