Monday

Yesterday was Valentine’s Day. After fifteen years together, Ron and I don’t take much notice of it. Oh, in the beginning there were flowers, and chocolates, and little gifts. My first to him was a silver razor inscribed “Good Morning, Love,†which he still uses. He gave me a basket of daisies and carnations and lavender statice, more light-hearted and longer-lasting than the traditional roses.

These days Ron takes the “Don’t-You-Hate-Clichés†approach to Valentine’s Day. It is, he maintains, an invention of card manufacturers and flower vendors, and he doesn’t need corporate America to tell him when and how to express his love. I might have shared this view in my anti-establishment hippie-dippie days, but I’ve gotten more sentimental in my dotage.

For years, however, I’ve said that the only gift I want is a love letter. He says he doesn’t do love letters, especially at Valentine’s Day (the spurning corporate America thing again). Our daughter at 13 neither expects nor wants a Valentine from her parents, so the day passes without much hoop-de-do.

But we did talk about love, and romance, and the mysteries of the heart this weekend. Ron’s aunt died in December, and we’re now in the process of preparing her house for sale. Ron comes back from every session in her attic or her closets carrying some new treasure — an army uniform, a box of letters, a folder full of pictures.

Her name was Ezenne, an unusual choice, I always thought, for the daughter of Italian immigrants whose other children bore recognizable saints’ names. She was born in 1918 in Hershey, Pennsylvania, not far from the intersection of Chocolate and Cocoa Avenues (“the chocolate crossroads of the worldâ€), where the street lamps are shaped like Hershey’s Kisses and you can’t find a bar of Nestle Crunch to save your life.

She graduated from Hershey High School in 1936 and spent the next 49 years as a clerk in the billing department of Hershey Foods. She never married, was known by many as “Aunt Nanny,†and was remembered at her funeral as a faithful member of the Altar & Rosary Society and the Sodality of Mary.

She was nearly 65 when I met her, a woman who loved escorted bus trips to places like Carlsbad Caverns and doted on the children of her niece and nephews. She wore her hair in a teased beehive that she kept dyed a dark brown. It looked like a Carmen Miranda hat without the fruit and though it added about four inches to her height, it still didn’t help her clear 5’3. Most of her clothes were brown, and we didn’t have much in common beyond a mutual interest in my daughter. Only now, in the memorabilia being retrieved from her home, am I beginning to form a picture of the young Ezenne.

The family story has come to me in bits and pieces. Aunt Nanny was once engaged — that explains the silver-framed picture of a handsome young man visible on the end table in family group shots from the war years.

His name was John. He was from Pittsburgh. She met him when he was stationed at Indiantown Gap, a training facility not far from Hershey. He was amiable, well-spoken, Catholic. He was perfect.

Before he shipped out for Italy he gave her a ring. They wrote to each other faithfully, although those letters, if they still exist, have not yet been found. Letters from Ezenne’s brother express the hope that he’ll be home in time to be best man for a wedding in the summer of ’46.

When the war ended, John decided to stay on in the service. He’d put in ten years already, and saw an Army career as the right path for him. Together, he and Ezenne could travel the world. But Ezenne didn’t want life as an Army wife. She didn’t want to move around, live in rented quarters, be a rootless sojourner, no matter how exotic the place. She wanted John to get a job in Hershey. Each hoped to change the other’s mind. It didn’t happen.

My husband, eight years old at the time, remembers the night the ring was returned. He sat in the kitchen with Nonna, who made busywork while she muttered “Dio, Dio, Dio,†as she had the night the war began. Afterward there were tears, and John’s picture was removed from the end table, and in time no one talked about him anymore.

In the years that followed, Ezenne dated from time to time, but nothing ever turned serious. John stayed in the Army, married and had a family. After he left the service he settled back in Pittsburgh. When he passed away in 1990, his daughter called with the news, saying her father had left instructions that Ezenne be notified. His wife died a few years later. They are buried in the national cemetery at Indiantown Gap, only two or three rows from where Ezenne’s brother lies.

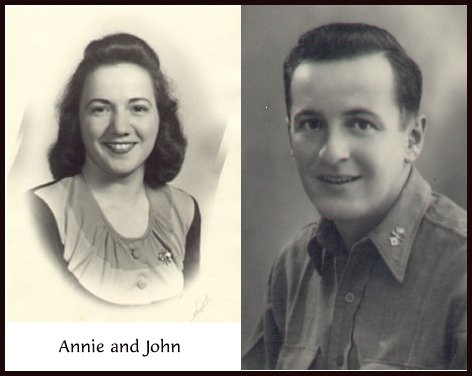

This weekend my husband brought home some pictures from those engagement years. One is a formal portrait of Ezenne. Her hair is in a long loose pageboy, and the smile she shows the camera is full of youth and joy. She wears a scoopneck dress, with John’s Signal Corps pin riding just above her heart. A portrait of John reflects the same young energy. It was taken in Italy, and on the back he wrote, “Annie Dear, I will always love you. Miss you something awful. Johnny.â€

Annie dear. Annie. He had a special name for her, something no one else ever called her. He said he would always love her, and I’m certain he always did. I am even more certain that she always loved him. When I look at her picture now I see Annie, and I see with new eyes.

Â

Love it? Hate it? Just want to say hi?

To comment or to be included on the notify list, e-mail me:

margaretdeangelis [at] gmail [dot] com (replace the bracketed parts with @ and a period) OR

Follow me on Twitter: http://twitter.com/silkentent