No Brief Candle

A Family History Project

July 11, 2001

Wednesday

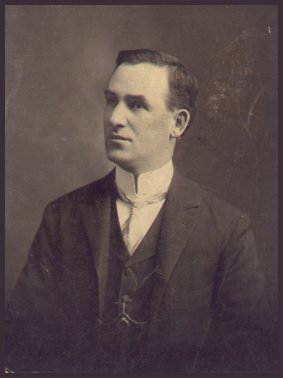

My

maternal grandfather, Michael Patrick Dwyer, is pictured at left as a young

man, probably at the time of his wedding in 1901. He was born in 1864,

one of ten or so children of impoverished Irish immigrants. He left school

at ten to become a slag picker in the coal fields of Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania.

Bright and energetic, he educated himself, read widely,

and in his mid-twenties passed the government examination that made him

a mail carrier. It was his labor that supported his widowed mother

and his siblings, including the seminary training of his brother Will,

who died of consumption two months short of ordination. By the time

he was in his thirties, Mike was secure by coal region standards, and he

was able to marry and start his own family.

My

maternal grandfather, Michael Patrick Dwyer, is pictured at left as a young

man, probably at the time of his wedding in 1901. He was born in 1864,

one of ten or so children of impoverished Irish immigrants. He left school

at ten to become a slag picker in the coal fields of Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania.

Bright and energetic, he educated himself, read widely,

and in his mid-twenties passed the government examination that made him

a mail carrier. It was his labor that supported his widowed mother

and his siblings, including the seminary training of his brother Will,

who died of consumption two months short of ordination. By the time

he was in his thirties, Mike was secure by coal region standards, and he

was able to marry and start his own family.

He married Margaret Waters, a woman nearly fourteen

years younger than he. Their wedding took place in September of 1901, and

part of their wedding trip was spent watching President McKinley's funeral

train pass through Niagara Falls. Despite having this as a central honeymoon

memory, their union was happy, producing three children, of whom Rose,

the youngest and second daughter, became my mother.

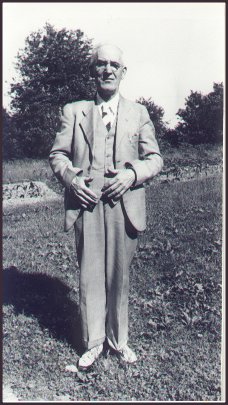

Rose

adored her father, and anything I know of him I know from her. He is pictured

at right a few months before he died in 1940. Not long after that my mother

had to leave a showing of the popular Academy Award winning movie Gone

With the Wind because Scarlett O'Hara's father reminded her too much

of her own. I wasn't born until 1947, and from the moment she knew she

was pregnant, my mother was determined to name her child Michael, to honor

him. When I turned out to be a girl, she called me Michael anyway, switching

to her mother's name only after friends implored her to think the matter

through.

Rose

adored her father, and anything I know of him I know from her. He is pictured

at right a few months before he died in 1940. Not long after that my mother

had to leave a showing of the popular Academy Award winning movie Gone

With the Wind because Scarlett O'Hara's father reminded her too much

of her own. I wasn't born until 1947, and from the moment she knew she

was pregnant, my mother was determined to name her child Michael, to honor

him. When I turned out to be a girl, she called me Michael anyway, switching

to her mother's name only after friends implored her to think the matter

through.

Thus

my maternal grandfather is a shadowy figure, an idea rather than a person.

Nevertheless, I have something in his hand, a postcard he sent my mother

on September 4, 1940. The message, which is written in pencil, reads, "Dear

Rose, We came home last night. Mother had got through with what She wanted

to do for Mary and we brought Eddie up. John is down helping Jim on the

lot, and Mary is in the store. Mother and Eddie is gone to the show this

afternoon. Hoping you will have a nice week end I remain as ever, Your

Dad."

Thus

my maternal grandfather is a shadowy figure, an idea rather than a person.

Nevertheless, I have something in his hand, a postcard he sent my mother

on September 4, 1940. The message, which is written in pencil, reads, "Dear

Rose, We came home last night. Mother had got through with what She wanted

to do for Mary and we brought Eddie up. John is down helping Jim on the

lot, and Mary is in the store. Mother and Eddie is gone to the show this

afternoon. Hoping you will have a nice week end I remain as ever, Your

Dad."

Some things I know for facts, others I can deduce. September 4 was a

Wednesday that year. I suspect the picture was taken the previous weekend,

which was the Labor Day weekend. I have another which shows my grandparents

and other relatives along with my mother, gathered around her new car,

a black 1939 Chrysler. My grandfather is wearing the same suit, quite an

outfit for a sunny summer day. My mother remarked once that she had seen

her father only once without his vest and his collar in place. Mary is

their older daughter. She and her husband Jim live in Summit Hill, a small

town about twenty miles east of Mahanoy City. They operate a small general

store. I do not know who John is nor what "helping Jim on the lot" might

entail. Eddie is Mary and Jim's three year old son. The card is addressed

to my mother in Harrisburg, the capital city where she has been living

for four years

The postcard is an unremarkable document. It's a standard post office

issue, prestamped with one cent postage (a green engraving bearing a portrait

of Thomas Jefferson). I found it among the cartons of unsorted memorabilia

I acquired after my father died, and for a long time I wondered why my

mother would have bothered to keep it, since its message is unremarkable.

It was several years before it dawned on me -- this was the last thing

she had of him.

Although I live by the written word, I have not had occasion to exchange

many letters with members of my family. I attended college only forty miles

from my home town, my sister a different school ninety miles away. By then,

of course, there was the telephone, and more cars to travel over better

roads, and we never spent long periods apart. I do have one letter from

my father, sent in the summer of 1972 to Duke University, where I was studying

Shakespeare. It's a letter not unlike the postcard in that it doesn't say

very much, certainly nothing of lasting significance. It is remarkable

only for the fact that he has spelled my name wrong, writing "Margie" for

"Margy" (which, if you please, is pronounced with a hard g), an

understandable mistake for one who had certainly never seen my nickname

written down.

We have e-mail now, of course, and after I finish this piece I will

compose such a note to my daughter, now enjoying two weeks at camp. I've

urged her father to write something as well. It won't be in his hand, but

I know she saves these missives, which the camp staff print out and distribute

each morning, all the electronic routing headers intact. In this regard

e-mails are even less aesthetically pleasing than a yellowed penny postcard.

But what they represent is invaluable.

(Previous

-- Next)

This journal updates irregularly.

To learn when new pieces are added,

join

my Notify List.

Return

to The Silken Tent Main Page

Return

to No Brief Candle Index

The

contents of this page are © 2001 by Margaret DeAngelis.

This

site is hosted by Dreamhost.

They're dreamy!

My

maternal grandfather, Michael Patrick Dwyer, is pictured at left as a young

man, probably at the time of his wedding in 1901. He was born in 1864,

one of ten or so children of impoverished Irish immigrants. He left school

at ten to become a slag picker in the coal fields of Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania.

Bright and energetic, he educated himself, read widely,

and in his mid-twenties passed the government examination that made him

a mail carrier. It was his labor that supported his widowed mother

and his siblings, including the seminary training of his brother Will,

who died of consumption two months short of ordination. By the time

he was in his thirties, Mike was secure by coal region standards, and he

was able to marry and start his own family.

My

maternal grandfather, Michael Patrick Dwyer, is pictured at left as a young

man, probably at the time of his wedding in 1901. He was born in 1864,

one of ten or so children of impoverished Irish immigrants. He left school

at ten to become a slag picker in the coal fields of Mahanoy City, Pennsylvania.

Bright and energetic, he educated himself, read widely,

and in his mid-twenties passed the government examination that made him

a mail carrier. It was his labor that supported his widowed mother

and his siblings, including the seminary training of his brother Will,

who died of consumption two months short of ordination. By the time

he was in his thirties, Mike was secure by coal region standards, and he

was able to marry and start his own family.

Rose

adored her father, and anything I know of him I know from her. He is pictured

at right a few months before he died in 1940. Not long after that my mother

had to leave a showing of the popular Academy Award winning movie Gone

With the Wind because Scarlett O'Hara's father reminded her too much

of her own. I wasn't born until 1947, and from the moment she knew she

was pregnant, my mother was determined to name her child Michael, to honor

him. When I turned out to be a girl, she called me Michael anyway, switching

to her mother's name only after friends implored her to think the matter

through.

Rose

adored her father, and anything I know of him I know from her. He is pictured

at right a few months before he died in 1940. Not long after that my mother

had to leave a showing of the popular Academy Award winning movie Gone

With the Wind because Scarlett O'Hara's father reminded her too much

of her own. I wasn't born until 1947, and from the moment she knew she

was pregnant, my mother was determined to name her child Michael, to honor

him. When I turned out to be a girl, she called me Michael anyway, switching

to her mother's name only after friends implored her to think the matter

through.

Thus

my maternal grandfather is a shadowy figure, an idea rather than a person.

Nevertheless, I have something in his hand, a postcard he sent my mother

on September 4, 1940. The message, which is written in pencil, reads, "Dear

Rose, We came home last night. Mother had got through with what She wanted

to do for Mary and we brought Eddie up. John is down helping Jim on the

lot, and Mary is in the store. Mother and Eddie is gone to the show this

afternoon. Hoping you will have a nice week end I remain as ever, Your

Dad."

Thus

my maternal grandfather is a shadowy figure, an idea rather than a person.

Nevertheless, I have something in his hand, a postcard he sent my mother

on September 4, 1940. The message, which is written in pencil, reads, "Dear

Rose, We came home last night. Mother had got through with what She wanted

to do for Mary and we brought Eddie up. John is down helping Jim on the

lot, and Mary is in the store. Mother and Eddie is gone to the show this

afternoon. Hoping you will have a nice week end I remain as ever, Your

Dad."